View this episode's trailer

Episode Description

“Mother Nature doesn’t really care about our patent system. Things work or they don’t work.”

Dr. Moss continues telling his story of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Laetrile coverup, his early experience with challenging the medical establishment and the personal and professional costs of telling (and not telling) the truth. Dr. Moss reveals the way drugs come to market and why so many treatments that can help patients aren’t prescribed, let alone make the headlines.

So, when the day came that Dr. Moss was MISTAKENLY told that he had advanced metastatic prostate cancer and there was nothing that could be done for him, how did he respond?

Listen to hear the end of his inspiring story!

For over 40 years Dr. Gary Onik has been pioneering advances in cancer treatment that have rocked the field of oncology, inventing an entirely new branch of cancer treatment now known as “Interventional Oncology” based on his innovative minimally invasive techniques. Both doctor and patient, he created a cancer vaccine and successfully treated his own terminal prostate cancer using his invention. In addition to his medical practice, Dr. Onik is an Adjunct Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, working closely with his colleagues to develop the next generation of cancer fighting technologies. His latest work, using immunotherapy to treat metastatic cancer, offers hope to those patients with literally no other options.

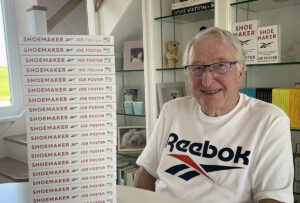

Host

Dr. Gary Onik

garyonik.com

Guest

Dr. Ralph Moss

mossreports.com

IMMUNOTHERAPHY: THE BATTLE WITHIN | 2020 DOCUMENTARY immunotherapyfilm.com

SECOND OPINION | 2014 DOCUMENTARY secondopinionfilm.com

TRANSCRIPT

Dr. Gary Onik [00:00:00] Hello, I’m Dr. Gary Onik, and I’m your host for Cancer is Tough, but YOU are TOUGHER! I want to thank The Beach Boys for allowing us to use their piece of music that is dear to my heart. My podcast is uniquely personal. I know both sides of the cancer equation. I am a cancer specialist and researcher, as well as a cancer patient and survivor. I will address various treatment modalities in the podcast, but that’s not really what this podcast is about. This podcast is about the unique cancer journey that a patient and their family and friends take when they are diagnosed and treated with this dread disease. We’ll delve into the inner emotional and spiritual resources. Patients and their loved ones need to address their concerns of choosing a treatment strategy that will harmonize with their worldview while grappling with state-of-the-art treatments versus alternative treatments. When I was asked who’s going to be my target audience, the obvious answer was everyone. It’s a rare person that has not had cancer touch their lives, either as a patient, a family member or friend. If you’re that rare person that hasn’t had cancer touch their lives, almost certainly at some point, cancer will drag you into its maelstrom. I hope that you find this show both a resource and a comfort in dealing with your cancer journey.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:02:07] It’s a pleasure to have Dr. Moss back for the second half of this interview. If you have seen the first episode, I’m sure you’re going to enjoy this second episode. We hope you enjoy our show.

Dr. Moss [00:02:39] The next one I saw was Bob Good. Bob Good was a famous person. He’d been on, his face was on the cover of Time magazine in 1973. He was the big boss at Sloan Kettering Institute. I actually not only got to meet him, meet with him because of course I knew him, but he and I went out to have dinner together at 21 Club. Pretty heady stuff, but in any case, there we are, having dinner together at 21 Club and I brought it up. I have to; I mean, I brought up this the issue. I brought up the non-agreement between what we were saying or what he was saying and what the actual results were. And his response was, you know, Ralph, I’m just like you. I said, really? He says, yes, I can be fired, and you can be fired. That was all he would say.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:03:35] Wow.

Dr. Moss [00:03:36] Pretty clear where I was heading with all of this. Now, of course, the interesting part, OK, the fourth one, the fourth one that I had to see—well, there were two vice presidents at Sloan Kettering. Good was the president, and the two vice presidents were Chester Stock who was a dyed in the wool chemo guy, and Lloyd Old who was actual spirit behind doing the laetrile experiments in the first place. And Lloyd was a wonderful, wonderful scientist and a wonderful person. And he wouldn’t see anybody. He had walled himself off from the rest of the institute and the rest of the center. He had his own thing going and he agreed to see me because I had written some articles that he liked for the Center News, which was our in-house publication. So, he agreed to see me. And it was so different from any other lab or office you’ve ever seen in your life. Big portrait of Mozart on the wall. He was an expert violinist. He was like a professional level violinist. He had rugs that were beautiful… couch. It was amazing. And we started talking about this stuff and he was… It was different. You were dealing with a genius person, but not an eccentric… You know, geniuses can come in all varieties of personality, but a sensitive artistic person with fabulous scientific sense, just a great person. And when I brought up the thing about laetrile and we talked about hydrazine sulfate and about some of the other Livingston, some of the other controversies. And he said to me: Ralph, do you want to know where we get all our new ideas from? Well, of course, I wanted to know where they got all their new ideas from. He got up, he walked behind me to the bookshelf, took down a book, handed it to me. It was the quack list. It was… It was unproven methods in cancer management. It was the same book that I had been handed on the first day to warn me away and to warn the public away from all of these quacky treatments. He says, here this is the Bible. That changed my life. Long story short, and I’ve written a book about this—to put it on the record—called Doctored Results and then Eric Merola made a film about it, about my days at Sloan Kettering, which was called Second Opinion. It’s a bigger story than this. Anyway, it’s all very simple. I mean, they fired me in 1977 for… basically, I wrote the press release that condemned laetrile to oblivion and saying that they had… I had no choice because I knew my days were numbered there and I wanted to learn as much as I could while I was still there. I wasn’t just going to go out and quit or just get another job. I didn’t want to do that even though I had two little kids at home. We had, my wife and I, had two kids at home. But anyway, I then refuted my own press release that I had written, my own report. I wrote another report and we distributed that, and I stood up at a press conference at the Hilton Hotel in Manhattan, said all of these things, and they fired me the next day. New York Times said I failed to carry out my most basic job responsibilities. So that was it, I had gone against the boss.

Dr. Gary Onik Amazing.

Dr. Moss Had complete support from my wife, my kids, my mother, my father too, but especially from my mother; all stood behind me, all supported me. My wife literally supported me for the next three years. I had no income. I couldn’t get a job. That’s why I made breakfast for her every morning, for the last thirty-five years because of my gratitude for her, for having been the breadwinner while I wrote The Cancer Industry, which was my answer to them firing me. But why? So, what’s the commonality? There were two things about it. First of all, don’t challenge the establishment in any field because these are mafiosi. You know, these are the mafia.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:08:10] I wish you could have told me yesterday. It would have made my life, my career so much easier. If you had let me know about that.

Dr. Moss [00:08:19] I did let you know. You just didn’t read the book. That’s all.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:08:22] You know it.

Dr. Moss [00:08:24] The first thing is, it was a challenge to… because there was a movement and the movement had a core, and the core was the John Birch Society. Nobody else would touch this thing, and it felt… it could conceivably have fallen to a left-wing group, but that’s not too likely. It fell to an extreme right-wing. I would call John Birch Society an extreme right-wing group because they were not tied to either the Democrats or the Republicans. They had been condemned by both, and they were sort of, you know, on the outs with the political and cultural establishment. And this was not where I was coming from, you know, by any means. I didn’t think that politics should deter, you know, the apricot kernels didn’t have, they weren’t leftist or rightist. They were just what they were. And they either worked or they didn’t work, you know, and it didn’t matter. There were people of different political persuasions involved in this whole thing. And yet it got stereotyped as a right-wing conspiracy. And more than stereotyped, I mean, they were brought up on charges and some of them were convicted and smuggling and commercializing a drug without, you know, FDA’s permission. So, it was a challenge to the FDA. I can understand that. They were rigid in this, but they tend to be very rigid because they’re trying to hold on to their power. I’m not against there being an FDA. I just think that, you know, they should be a little more accommodating towards the consumer, towards the patients and allow people… And now you have a bit, a bit of a loosening of that. The other bigger issue, much bigger, was economic. And if you look at the big picture you look at all—now we have 1,400 supplements out there that conceivably could be used for cancer, and it’s a $100 billion business. One drug alone, Keytruda, I think that they racked up $8.8 billion in sales two years ago and Keytruda, it’s probably over $10 billion by now. So, we’re talking about, you know, huge business numbers that we can’t, couldn’t have comprehended 40 years ago at all. And so, what makes for a drug nowadays, since it costs hundreds of millions to create a new drug, you know, the drug companies have to charge a lot of money for these things. And in order to do that, the linchpin of it is the patent. The patent—and you’ve gone through the patent process yourself many times, I know that—but the strength of the patent is the most important thing. And none of these things that circulate around in the naturopathic community or the holistic medical community, whatever you want to you call it, I mean, with rare exceptions, these things are not patented. And plus, the way that the things have fallen out in the United States, either it’s a supplement or it’s a drug. If it’s a drug, you’ve got to spend hundreds of millions. Supplements, of course we have a very liberal attitude in the U.S. about supplements, but you can’t make any health claims. So, you’re, there’s no point to doing research, intensive research on these things, unless you’re a masochist because you’re never going to get FDA approval for a supplement to treat… well you won’t. I saw this in ’75 and I wrote about this. This was the whole point of my book Cancer Syndrome, which we titled as Cancer Industry in 1980. And I had read it. I mean, I had come across documents in the archives at Sloan Kettering saying, the patents will control the future of cancer research and cancer treatment. This was written by one of the leaders of Sloan Kettering in 1939 or 1940. He gave a speech to the patent attorneys. I read this; it was in the… I don’t have it anymore, but it was in the archives of Sloan Kettering itself. So, this is well known in the field. It’s the most… it’s the ABC’s of drug development. But Mother Nature doesn’t really care about our patent system. Things work or they don’t work, or they could be helpful or not helpful. So, it was more than just laetrile. Laetrile if it had been approved, would have opened the floodgates to a whole slew of natural treatments, many of which are probably a lot better than laetrile ever was. I’m not an enthusiast for laetrile. I’ve never recommended laetrile even once to a client of a consultation, client of mine. It’s toxic in high doses. If you took too much curcumin, you might get a stomach ache; if you took too much laetrile you could die of cyanide poisoning. So, it was a bad test case because it really fell and falls between the supplements and the drugs. And the cyanide was there for a purpose because they wanted that cyanide to be there because the theory was that, oh, it’ll kill the cancer cells, but the normal cells will be protected. People have died from excessive intake of laetrile. I don’t want those deaths on my conscience. Plus, it’s a long story and we weren’t, we have no time for it, but there is no human data on the effectiveness of laetrile. It more or less stopped at the level that Sugiura established. There have been about 30 other experiments in the laboratory showing that it is anticancer, so I don’t think there’s any doubt. Even if we didn’t know anything about Sugiura, you would say that, yeah, this is like a curcumin, or like an AGC gene or one of the, you know, soy isoflavones. Maybe not quite as good, but it’s in that same phytochemical category, but because of the cyanide that’s contained naturally in the apricot kernels, it falls into a somewhat different category, and FDA was not prepared to deal with that. They saw it as a big danger. But the bigger danger was that if you could make health claims for a natural substance like that, that was very cheap… in essence, if the price had been jacked up tremendously by smugglers and importers or whatever… But it’s essentially a waste; comes from a waste product. What other, you know, how many uses are there for apricot pits or black cherry seeds or so. It’s a cheap, inexpensive thing that could have been provided to everybody at virtually no cost. And all those things, and there’s hundreds of them, are… it’s forbidden, basically, to take them any further than the underground movement; than the supplement movement. And occasionally something slips through, but it’s squelched. And that’s… you could call that a conspiracy. I don’t see it as a conspiracy. I spoke out against conspiracies in 1977. I think it’s business as usual.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:16:10] It’s what you’d call a conspiracy of interest. Everybody has the same interest, and so it looks like a conspiracy. But it goes a little deeper than that, Ralph. I mean, you can go back in medical history and you’re a medical historian. You know the story of Semmelweis?

Dr. Moss Yes.

Dr. Gary Onik He was someone who had a simple method of saving tens of thousands of women’s lives from puerperal fever infection after childbirth. He proved it unequivocally and yet, in his lifetime, they did not give him the credit for it or take up his methods. I mean, there is just something that that is contrary about the medical profession that does this every once in a while, no matter how important it is.

Dr. Moss [00:17:05] True. And I think it’s every profession, but it’s much more intense in medicine because you are called upon to make life and death decisions. You are recommending a course of action as a physician that people rely on for their very lives. And you’re also an expert. If you’re an expert, you can’t be wrong, you know, because the prestige of your position is that you are the source of wisdom on this and on these questions. A lot of doctors and leaders had foolishly gone out on a limb and said laetrile doesn’t work and now blah blah blah. It’s terrible and stay away from this and so forth. Any then along comes an honest scientist, Sugiura, who says, I write what I see. And he could not be persuaded. He wasn’t a samurai. His ancestors were, but he was a kendo and jujitsu expert. He toured the United States. He had performed in front of Teddy Roosevelt at the White House. He was a very strong, determined person, unique. I used to say that he was a pathological truth teller. Because when it came time and they were suspecting me of having leaked the documents, he wouldn’t lie on my behalf. I didn’t ask him to. But you know what I mean? He couldn’t have. He couldn’t, even though I’m sure he didn’t want me to get fired. But he couldn’t lie just because of that. He was a pathological truth teller. I mean, I joke, I’m joking. It’s nothing pathological about it. But he was just one of those people. You were not ever going to get this guy to twist the truth in one degree difference. So, this was one of those moments where the truth slipped out and everybody else ran for the hills. OK? I don’t know why I didn’t. As I said, I have fantastic support in my family. Even though we didn’t have much money. I think I had $2,000 to my name after 10 years of marriage, but we had moved and we had come back from Stanford and everything. But my wife totally supported me. My son, who’s now in business with me, basically runs The Moss Report, he was 10 years old at the time and he said the night that I had to make up my mind, whether or not to come forward and own what I had done; own this second opinion, special report on laetrile at Sloan Kettering; he said to me, you know, dad, you can’t go on working for them and against them forever. That was the attitude that my son, my 10-year-old son had. Everybody who mattered in my life supported me. So, you know, I’m only brave when I have some support. I mean, this was, you know, yes, it took a lot.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:20:20] Using that as a segway, you know, you went through a personal experience with cancer, I know. And I know that the support that you get from your loved ones is a critical aspect in that whole mix of things. Can you tell us a little bit of the story of how you found out and the process you went through to decide what you were going to do? And, you know, was there any insight in your Father Damien moment?

Dr. Moss [00:20:54] So I had a somewhat elevated PSA for some years. I had also had chronic prostatitis. So, I had pain, and at times I had even had some bleeding, just trace amounts of blood. My digital exams were always normal, and the PSA, you know, was in the range of four, something like that. So, it crept up very, very slowly on me. And then I took an unconventional test for cancer. I had a good friend and colleague, Jim Moray, who was a professor at Purdue University in Terre Haute, Indiana, and he had devised a test called ANCA Blocked. I was very interested in this test. We were recommending it to people. And I thought, well, my wife and I should get this test done because I’m talking about it so much and I should know firsthand. All right. My wife turned out just fine and mine came back saying, you have prostate cancer. Well, the test was uber sensitive that you could look at smallest amount of cancer would show up on this. That was one of the limitations, one of the problems with the test; that it was so sensitive. I was so sure that I had a nonmalignant malignancy. In other words, a PIN which was like a pre-cancer. I even wrote out PIN on my desktop, and I put it there to remind myself, well, this is really no big deal. But at that time, just at that moment, this was six, seven, six years ago. Some people had started to do MRIs in advance of biopsies. I didn’t want to have a biopsy. The last thing in the world I wanted was to have some person poking holes in my tender parts. My urologist told me there’s no way on earth that you have an aggressive prostate cancer, this is what she said. Absolutely not. You’ve got… the free PSA was falling and the PSA was rising. It was now over 6, 6.6 I think was the high point. I don’t know why she thought that, but in any case, she said we could do a biopsy. I don’t want a biopsy. I just don’t want it. I’m too afraid of infection and everything else. So, I want an MRI and I want a 3 Tesla Magnet MRI, which was the latest, greatest thing at that point. And they didn’t have it where I was living at the time. So, my wife and I drove to Philadelphia. Had an MRI, 3T MRI done at Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and then I went… I got the report. I couldn’t really make too much sense of it, but I got the appointment with the guy who was now being promoted within that department. But anyway, one of their urologists comes in, doesn’t look me in the eye, doesn’t look at my wife, shuffles over to the computer, says his last name by way of introduction. Real charmer; never looked at me once. Never looked. Never, of course, never touched me, but never looked at me. No examination. And the first things out of his mouth are, you’ve got advanced cancer. It’s two very large tumors. It’s outside the capsule and there’s nothing we can do for you. Basically, we could give you radiation, but it’s just going to prolong your life. There’s nothing…. This was the introduction and went downhill from there. I said, I don’t understand this because I mean, I read the radiology report and I saw that there were two tumors, but I didn’t see anything about it being outside the capsule. In other words, having metastasized or spread outside the, you know, immediate area. I said, could you do me a favor? Could you put the MRI images up on the screen so that my wife and I can look at it so I can see what you’re talking about? He got furious. He said, he screamed. He said, I’m a urologist, I’m not a radiologist. The radiologists read the images. I just report what the radiologist sees. This is what he told me, and he scheduled… and actually got so cowed by this that I scheduled a biopsy for the next Monday. This is a Friday. I was the last patient of the week. I figured I better grab this appointment for Monday. So, I went back, and I had met and kind of knew a naturopathic doctor who was at NYU. I said that Eric Merola had made a film about my years at Sloan Kettering. They actually had a theatrical release in Manhattan, and Gio, his name is Gio Espinosa, had come to the screening of the opening of the film in Greenwich Village. So, I had his number and I called him. I called him just and I told him this story of what had happened. And Gio said, look, I’m not going to self-advertise and tell you, you have to come to NYU, but I just want you to know that, you know, that’s available to you. You could come here and please—this is what he said that influenced me and basically, I think it may have saved my life—do not make any commitment to do anything further without consulting with the doctors here at NYU, at least get a second opinion from them. And he gave me the name of the doctor, the most appropriate doctor who was Samir Taneja. So now I probably said at that time, I’m not recalling, but I’m almost certain that I had and I said, you know, what I really want? I don’t want radiation. I don’t want surgery. I don’t want radioactive seeds. What I really want is ablation and particularly cryoablation, because I knew about cryoablation. I knew about… I’d read your book, Gary, The Male Lumpectomy. I mean, the words The Male Lumpectomy just jumped into my head, you know, it made so much sense. It made so much sense when I read it and especially when I had the disease and I thought, wow, if I could just get them to just take out that tumor, then, either it’s going to work or it’s not going to work. If it works, I’m home free. If it doesn’t work, they could reablate me or I could then go to the radiation or, you know, surgery. That was my thinking. So, I got an appointment with Dr. Taneja. It was night and day different, night and day different, from what happened to me at Penn. They couldn’t have been nicer, more accommodating. And I said, I’m only going contingent upon him showing us the slides. I want to see with my own eyes what is going on down there and to see whether this is… because now I was in mortal dread that this thing had actually spread. He did the biopsy, and I was up awake for the biopsy; it was very interesting. The bad news was two large, aggressive tumors, Gleason 8s both of them, Gleason 8’s, which is defined as aggressive, poorly differentiated, potentially fatal, dangerous kinds of prostate tumors. Two large ones. All of the samples came back more or less positive. Most of them 8s, a couple of 7s, but still, you know, very actionable and so forth. The good news was no, it had not spread out. Can you imagine? I’m over at an Ivy League medical center at Penn, and they give me that information which could… I swear I think I really got PTSD that day that they had told me that I. I haven’t been able to completely shake that feeling, that sinking feeling when you’re given a diagnosis that basically it’s a death sentence. And I know I’m preaching to the choir here, Gary. But you know, this was my wakeup moment. That was a tremendous relief, and the even greater thing was that he was perfectly fine with doing cryoablation on me. Haifu had just come in at that time, but they hadn’t figured out how they were going to bill for it. But I was interested in cryo because of you, because of your work and because of Aaron Katz, whom I knew in New York and Duke Bahn and other people who were using cryo around the country and around the world. So, I knew about the benefits of the abscopal effect and all that. I knew all that. But of course, when it comes down to your own person it’s a different story, entirely different. And I’ve said the difference between me pre diagnosis and me after diagnosis was exactly like what happens in the Wizard of Oz when it’s a horse of a different color. You know, when it goes from black and white to color, now you’re dealing with, you know, reality. Goethe said, theory is gray. And the good news was, yes, they did the ablation. I, you know, I got out of it what I wanted to get out. In other words, I didn’t have the problems of continence and impotence that were associated with some, you know, more commonly, I would say, more conventional diseases. I mean, there’s a lot of debate over what the percentages are. But when I read what they had to do in order to get you back to normal with surgery and radiation, I didn’t really want any part of it. So, this was great and I’m now approaching six years from the time of the procedure. The procedure was pretty much a piece of cake.

Dr. Gary Onik It’s wonderful.

Dr. Moss Pretty much a piece… I mean, the worst part of the procedure was the catheter that they had to put in, in order to make sure you can pee after, after they’ve done all that work. But he’s a masterful person, Tenaja. He has a sensitive touch. He doesn’t ablate too much. He doesn’t ablate too little. He’s a very good doctor and we’ve sent many people to him since then and everybody’s pleased with what has happened to them. It’s a great treatment. You are, really, I think you are the pivotal person. I know that there were people doing cryo in Westchester back in the ’60s, but you are the person, right, who basically put together image guidance with cryoablation, if I’m not mistaken.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:31:47] Yes, going back to ’82. We published our first article dealing with ultrasound.

Dr. Moss [00:31:54] Yeah.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:31:54] You know, ultrasound, and that opened it up because you finally had a way of harnessing it, seeing the tumor or seeing the ice and engulfing it. It was a heady time for us; it was a heady time. I mean, we finally had a way to cure things that couldn’t be cured in other ways.

Dr. Moss [00:32:10] It’s great.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:32:11] Yeah. And I was a young guy too.

Dr. Moss [00:32:12] Yeah.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:32:12] You know, I was… it was like your story, you know? On that note, on a positive note, I want to end this because we’ve talked about somewhat depressing things, but this was this was a happy ending.

Dr. Moss [00:32:29] It’s great for me.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:32:31] And I think that’s an appropriate way to say thank you so much for spending your time with us and giving us this very, very unique perspective. Thank you so much.

Dr. Moss [00:32:43] You’re welcome and thank you for having me.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:32:45] Can you give us specifics about how we get people to the website? And…

Dr. Moss [00:32:50] Sure, it’s simple. www.mossreports.com. We’re in the process of refashioning our website, but there’s a wealth of information there. You know, we have the product that keeps us alive, keeps us in business, which is the Moss Reports there. We now have, I think, reports on 40 different cancer diagnoses, so it’s pretty comprehensive. It covers most of the world of cancer, but we have a wealth of free information as well. Nobody has to buy anything. We have our film Immunotherapy: the Battle Within. We have my latest book there, Cancer, Incorporated and many, many articles and stuff. So, I hope people will come to the website, sign up for our periodic emails and so forth. We’d be happy to help them whatever way we can.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:33:49] This is the portion of the show where we talk about advances in oncology that should give our listeners hope. Today, I’d like to talk to you about checkpoint inhibitors. The checkpoint inhibitors, and I’ve mentioned them before, that are used currently and clinically for approved uses in oncology by the FDA are for checkpoints PD-1 and CTLA-4. So what’s a checkpoint? A checkpoint is a molecule on a lymphocyte or a cancer that turns off the immune system, and it’s a way for a tumor to escape the destruction by the immune system. So, what is a checkpoint inhibitor? A checkpoint inhibitor is a molecule that binds to that checkpoint and deactivates it so that your immune system can now recognize your cancer and kill it. So, there are two checkpoints, as I said, PD-1 and CTLA-4 that have already approved medications to allow you to manipulate the immune system and kill cancers with it. All of those commercials that you see on TV are about drugs that affect these checkpoints. So, what’s today’s news and the thing to be hopeful about? Well, there are numerous checkpoints which don’t have drugs made for them yet. And you can understand that the more checkpoints we find and the more drugs we produce and discover to affect those checkpoints, the greater the chance that we will be able to use immunotherapy to much greater effect in many, many different cancers. Right now, there is tremendous excitement in the immune-oncology world about a checkpoint called TIGIT and numerous companies, many of the large oncology, many large drug companies that have oncology programs are working toward getting anti-TIGIT drug on the market. There is some evidence now that that can be effective. Studies are still very early, but once anti-TIGIT gets approved, I expect that the overall immunotherapeutic cancer results will improve as well, and that will set the stage for a lot of other anti-TIGIT, anti-SPIGOT and any other anti thing you can make up. All these other checkpoints. So, it is a very hopeful thing, and that’s why you, as a cancer patient, should dedicate yourself to really trying to stay alive as long as possible, as long as your quality of life is reasonable because you never know when that drug that is going to save your life is going to be available. And you never know when that study is going to accept patients; that trial is going to accept patients, and you can be one of those patients in the trial and get this potentially miraculous result. And so, keep the faith. Have hope and keep fighting.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:38:18] Well, we come to the segment of our show where we answer questions from our listeners. These are questions regarding cancer and the patient’s journey and overall, the concepts associated with cancer. We do not discuss clinical situations for individual patients because there’s no possible way we can give you accurate answers unless we can see all of your information and medical records and we can’t do that. So don’t ask those questions because we’re not going to answer them. This question comes from Thomas from Dallas, and his question says “I’m dying from stomach cancer. My oncologist has recommended a clinical trial, but I only have a 50% chance of getting the new regimen. Should I enter the study?” Well, there are a couple of aspects to this question. As a cancer researcher who was involved in clinical trials, I would say yes, you should enter a clinical trial because if patients don’t enter clinical trials, we’re never going to get the information that we need to say whether one regimen is better over another regimen or if a new drug is efficacious and safe. So, I think the question for me would come down to is the regimen that they are going to compare something that I can get without being in the clinical trial. I mean, there are regimens that you can have with off label medications that are being tested in clinical trials for new indications. And you know, if you’ve reached the end of the road of the normal and usual treatments and this is a combination you can have because the medications are already available, then perhaps you can talk to your doctor and see if he’s willing to give you that regimen without having to be necessarily in the study.

Dr. Gary Onik [00:40:34] If you would like to ask us a question for the mailbag, you can go to garyonikmd.com. There is a contact form that you can fill out that will be forwarded to us, and we’ll consider your question for our show. Thank you for listening to our podcast. I hope that it provided you with some useful information, some hope and some comfort. Thank you very much.